Introduction

In the mist-laden pine forests of northern Wisconsin, where morning light barely pierces the dense canopy and the air hangs heavy with resin and the earthy breath of moss, stories have always lingered like woodsmoke. This land, carved by glaciers and shaped by ancient lakes, is a place where myth and reality often mingle. In the 19th century, as waves of settlers and loggers pushed into these wilds, Rhinelander was just a patchwork of cabins, sawmills, and dirt roads hugging the banks of the Pelican River. Yet even as axes rang and trees tumbled, the woods held secrets older than any settlement—a sense that something watched from the shadowed thickets, something primal and unknowable.

It was in this world of towering white pines, shifting fog, and echoing loon calls that the legend of the Hodag took root. The first whispers came from weary lumberjacks swapping tales after long days in the logging camps. They spoke of a beast with glowing green eyes, formidable horns, and jaws bristling with dagger-like teeth—a creature part lizard, part bull, and entirely ferocious. To some, the Hodag was a warning; to others, a challenge or a joke taken too far. Yet as stories spread, the line between jest and belief blurred. The Hodag became more than just a campfire phantom—it was a symbol of the mysterious Northwoods, a guardian of secrets, and eventually, the pride of Rhinelander itself.

This is the story of how a creature, born from tall tales and a masterful hoax, transcended its origins to become a living legend—a creature woven into the identity of a town, and a testament to the enduring power of imagination in the heart of Wisconsin.

Whispers Among the Pines

The earliest days of Rhinelander were shaped by ambition and hard labor. Settlers arrived with dreams of fortunes made from timber and land, their hopes as tall as the pines they came to fell. Lumber camps sprung up along logging trails, and with them came men from every corner of the country—hardy, weathered, and starved for entertainment after days swinging axes and wrangling logs downriver.

Around smoky campfires at night, as the wind whistled through the trees and the hoots of distant owls mingled with the crackle of burning wood, stories became their refuge. Some tales were of home, some of heartbreak, but the ones that spread fastest were those that flirted with the unknown. No story captured the men’s attention like that of the Hodag. It began as a whisper—a rumor of something unnatural seen in the gloaming. A logger named Old Charlie, whose beard was thick with woodchips and whose eyes missed nothing, claimed he’d glimpsed the beast one foggy dawn. Its back was hunched, he said, its tail ridged with bony spikes, and its breath steamed in the chill air.

Skepticism, of course, was a logger’s armor. But even the boldest men paused to listen. The woods were vast, after all, and full of shadows. The Hodag’s description grew with every retelling: now it had horns curved like scythes and claws that left gouges in tree trunks. Some said it howled with a voice that could split a man’s skull. Others joked it was just a bear gone wrong or an invention to keep greenhorns awake at night.

Yet the stories took root, nourished by the deep sense of mystery that clung to these forests. Nights grew colder and the tales darker. Trappers reported missing dogs and strange tracks in muddy hollows. Hunters swore they found deer carcasses torn apart in ways no wolf could manage. Each new detail—each exaggeration—transformed the Hodag from a fleeting shadow into a beast that haunted dreams. The legend became a secret handshake among loggers, a badge of belonging in a land that demanded respect for its dangers, both real and imagined.

As winter’s grip tightened and snow pressed the world into silence, the Hodag became more than a tale. For those far from home, it was an explanation for things that couldn’t be explained. For others, it was an excuse—why a man hurried back to camp before dark, why logs sometimes vanished, why strange noises echoed in the night. In time, the Hodag would leap from the circle of firelight into the wider world. But in these early days, it lived only in whispers, growing stronger with every retelling, its horns sharper, its fangs longer, as mysterious and wild as the Northwoods themselves.

The Showman’s Hoax

By the late 1800s, Rhinelander was changing. Railroads reached deeper into the woods, mills hummed day and night, and the population swelled with families hoping for a better life. But amid progress, the town’s sense of wildness remained. No one understood this better than Eugene Shepard—a man who could spot opportunity where others saw only trees and mud.

Shepard was equal parts timber cruiser, prankster, and dreamer. He’d seen firsthand how stories could turn ordinary men into believers, how a good tale could turn a dreary evening into an adventure. As word of the Hodag spread beyond the camps—appearing in letters home, local gossip, and even early newspapers—Shepard saw a chance to make Rhinelander famous.

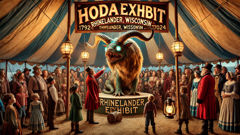

In 1893, he unveiled his masterpiece: the Hodag, captured at last. According to Shepard’s story, it took seven men armed with clubs, chloroform, and a healthy dose of courage to subdue the monster in a local swamp. The town buzzed with anticipation. Shepard, ever the showman, built a lair for the beast in a tent near his home and charged a dime for admission. What awaited inside was a spectacle: a hulking creature with green scales, fierce horns, bulging eyes, and rows of ivory fangs—constructed with wood, ox hide, cow horns, and clever mechanics. To the uninitiated, it was terrifying. Shepard rattled the beast’s cage and made it growl with hidden wires, sending shivers down many a spine.

People flocked from miles around—locals, travelers, even reporters—eager to glimpse the monster of legend. Some gasped in awe; others laughed nervously, unsure whether to believe. Shepard played to both sides, never quite confirming or denying the beast’s authenticity. The buzz grew so loud that a group of scientists from the Smithsonian Institution arrived to investigate. Faced with experts and the threat of exposure, Shepard finally admitted the truth: the Hodag was a hoax, born from local folklore and a healthy dose of frontier mischief.

But instead of dying, the legend flourished. Shepard’s genius wasn’t in fooling people—it was in capturing their imaginations. The Hodag became Rhinelander’s mascot, appearing in parades, business names, and local art. Children drew it in school; tourists sought out its lair. The line between fact and fiction blurred entirely. Where once there had been only whispers among the pines, now there was a story everyone wanted to tell—a story that belonged to Rhinelander alone.

Conclusion

Today, the Hodag is woven into the very identity of Rhinelander. Statues of the beast guard city parks and greet visitors at the airport. Schoolchildren learn about Eugene Shepard and his unforgettable prank, their laughter echoing down the halls. Local festivals celebrate the creature each year, with floats and costumes as wild and whimsical as the original tale. Tourists hunt for Hodag memorabilia, snap photos with its statues, and hike the piney woods where, if you listen carefully, you might still hear strange noises in the dusk.

Yet beneath the humor and spectacle lies something deeper—a reminder that every place needs its mysteries. The Hodag endures not because people believe in monsters, but because they believe in wonder. The forests of Wisconsin remain vast and full of secrets. Each generation adds its own layer to the legend: new drawings, new stories, new sightings whispered on chilly nights. In Rhinelander, the boundary between the real and the imagined is delightfully thin, and that’s just how people like it. The Hodag is more than horns and fangs—it’s a celebration of curiosity, creativity, and the power of a story well told.