Introduction

Shrouded in mist and veiled by time, the story of El Dorado begins high in Colombia’s emerald Andes, where the land undulates in deep green folds and clouds drift low across the ridges. On those cold mornings, when dew clings to the wild grass and the sun’s first rays gild the mountain lakes, it’s easy to imagine a world ruled by ritual and wonder. Among these peaks, Lake Guatavita rests—a near-perfect circle, its mirrored surface broken only by the ripples of wind or a wayward bird. Here, centuries before the arrival of armor-clad conquistadors, the Muisca people practiced rites older than memory. Their world shimmered with the promise of gold: not just as wealth, but as a sacred metal, a bridge to their gods. It was said that each new Muisca chieftain, or zipa, would undergo a rite of passage so spectacular it seemed the stuff of legend. Covered from head to toe in gold dust, he would stand atop a raft adorned with treasures, then step into the lake’s icy waters, washing away his golden mantle as offerings of emeralds, figurines, and delicate jewelry tumbled after him into the depths. To the Muisca, these acts ensured balance and favor with the divine, weaving gold into the very fabric of their world. But for outsiders, whispers of the Golden Man—El Dorado—became an obsession, a fever that would send men on perilous quests through jungle and mountain, chasing the promise of riches beyond imagination. This is not just a tale of lost treasure; it is the story of yearning, of how myth can outshine reality, and how a single ritual could ignite the hearts of generations. In the legend of El Dorado, we find both the brilliance and folly of humankind—forever searching for what glitters in the mist.

The Golden Man: Ritual and Reverence Among the Muisca

Long before any foreign sail caught the wind off Colombia’s Caribbean coast, the people of the Muisca Confederation had built a world shaped by ritual and respect for the unseen. They lived in harmony with the land, their villages ringed by potato fields and patches of maize, their temples standing in the open air beneath sky and sun. For the Muisca, gold wasn’t merely a symbol of power—it was the sun’s flesh, radiant and pure, a medium through which humanity might speak to the gods.

The crowning of a new zipa was the most sacred event in Muisca life. It was believed that the spirits of ancestors and the gods themselves watched from the heights as the time drew near. Over several days, the chosen heir was secluded, his body purified with incense and cool river water. The villagers sang ancient songs and crafted new treasures—thin disks of hammered gold, tiny frogs, jaguars, and birds rendered in dazzling filigree. These offerings were not for display or barter, but for sacrifice, destined to vanish into the dark belly of Lake Guatavita.

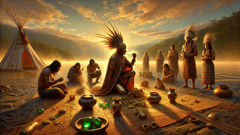

On the dawn of the ritual, the entire village gathered at the lakeshore. Priests painted the zipa’s skin with sticky resin, then dusted him with gold until he shone like a living sunbeam. He was led to the raft—a floating altar woven of reeds and adorned with golden idols, emeralds, and bowls heaped with coca leaves. Drums and flutes rose into the morning air, echoing across water and stone. The raft drifted from shore, pole-bearers guiding it toward the center of the lake. There, amid a hush broken only by bird calls, the Golden Man lifted his arms to the heavens. He cast treasures into the water—first with measured grace, then in wild abandon, as if flinging away the cares of all his people. At last, he dove, disappearing for a moment beneath the cold surface. When he emerged, goldless, the ritual was complete: the cycle renewed, the pact with the gods fulfilled.

These acts were never meant to inspire greed. The Muisca saw gold as a connector of worlds—its beauty a gift to be returned, not hoarded. Yet the stories of their rituals, told by traders and runaways, would become seeds of obsession. From the moment the first conquistadors heard of a man clad in gold, they burned with a desire not for meaning, but for possession. The legend would twist, take root, and send shockwaves through history—changing lives both native and foreign, forever.

Conquistadors and the Fever for Gold

The world beyond the Andes was shifting. In distant Spain, rumors of wealth in the New World fueled dreams of glory and fortune. Tales of golden empires—first the Aztec, then the Inca—stirred a tide of ambition across Europe. When word spread that somewhere in the highlands of New Granada, a ruler anointed himself in gold and cast treasures into a bottomless lake, the legend of El Dorado erupted into wildfire.

The first to arrive was Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada in 1537, his men gaunt from weeks of jungle and mountain crossings. They stumbled into Muisca lands—hungry, exhausted, and awestruck by the people they found. The Spaniards saw gold everywhere: in jewelry worn by nobles, in offerings at shrines, in stories whispered at dusk. Quesada’s chroniclers wrote of the zipa’s ritual as if it were a key to limitless wealth. The Spaniards soon learned of Lake Guatavita, where it was said the Golden Man had vanished beneath the surface, leaving gold and emeralds behind.

Driven by feverish hope, the conquistadors gathered their tools—axes, picks, and faith in their own destiny. In 1545, a group of Spanish officials attempted to drain the lake by cutting a gash in its rim. For weeks they watched as muddy water gushed through the channel. When the level finally dropped, teams waded into knee-deep muck, clawing through the silt in search of treasure. They found some trinkets—small disks, frogs, and earrings of pure gold—but nothing like the legendary hoard they’d dreamed of. Undeterred, they returned with more laborers and bolder plans. Again and again, over the next centuries, fortune-seekers would try to plunder the lake. Some lowered giant baskets. Others brought machines and dynamite. Always the lake resisted, swallowing their hopes as easily as it had accepted the Muisca’s gifts.

The quest for El Dorado spread far beyond Guatavita. Each new expedition ventured deeper into unmapped jungles, across rivers choked with mist and crocodiles. Englishmen, Germans, and even mad visionaries like Sir Walter Raleigh followed the rumor north, south, and east, convinced that a city of gold must lie somewhere just out of reach. None found it. Instead, many met only hunger, sickness, and the silence of the forest. For every legend of gold recovered, a dozen tales of loss and madness emerged. The Golden Man had become a ghost—forever ahead of those who chased him.

Echoes of Gold: Myth, Memory, and the Search for Meaning

Centuries passed. The dream of El Dorado faded from headlines, but never from memory. Lake Guatavita remained—a silent witness to all that had unfolded, its banks scarred by past greed, its depths holding secrets in silt and shadow. The Muisca themselves suffered under colonial rule; their numbers dwindled, their language and customs eroded by time and conquest. Yet the legend endured, woven into the fabric of Colombian identity and echoing across the world.

Archaeologists in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries took a more delicate approach. Instead of dynamite and shovels, they brought curiosity and respect. Divers recovered a handful of artifacts—delicate golden animals, tiny masks, and the most iconic find of all: the golden raft. Discovered not in the lake itself but in a cave near Bogotá, this intricate figurine depicted a chieftain surrounded by priests on a raft, arms outstretched as if mid-ritual. The artifact confirmed what chroniclers had written centuries before: that the legend was rooted in real ceremony and real belief.

Yet the true treasure was never gold. The story of El Dorado became a parable about longing—about how humans search for meaning in what glitters and gleams, sometimes missing the deeper beauty beneath. For the Muisca, gold had been a bridge to the divine; for the conquistadors and their heirs, it was a prize to be seized. In time, Colombians reclaimed the legend as their own, transforming El Dorado from a tale of conquest into one of resilience and cultural pride.

Today, Lake Guatavita is protected—a place of quiet pilgrimage, its waters reflecting both sky and story. Tourists and locals alike come to its shores, not in search of gold, but to feel the hush of ancient ritual, to see the place where myth took root. The golden raft gleams in Bogotá’s Museo del Oro, drawing visitors from every continent. Children hear the tale in schoolrooms; elders remember it as part of their heritage. The Golden Man lives on—not as a king lost to history, but as a symbol of what endures when greed fades and wisdom remains.

The legend of El Dorado asks us to look beyond surface glitter, to seek the riches that lie in memory, respect, and shared story. In the ripples of Guatavita’s waters, in the glint of a gold frog or a whispered prayer, we find the true heart of Colombia—and perhaps, a lesson for us all.

Conclusion

El Dorado was never just a place, or a man dipped in gold. It is a mirror—reflecting both the beauty and blindness of human longing. The legend of the Golden Man endures not because of the treasures lost beneath Lake Guatavita, but because it reminds us of how easily wonder can turn to obsession, and how deeply myths can shape our world. For the Muisca, gold was meant for gods and balance; for explorers, it was temptation incarnate. In chasing after a shimmer on water, they found hardship, but also stories that would ripple through centuries. Today, El Dorado is not a destination to be conquered but a mystery to be respected. The lake still gleams at dawn, and sometimes in its silence, you might imagine the zipa rising from the mist—gold dust glimmering, hands open, offering not riches but the hope that we might remember what truly matters: reverence, wisdom, and the quiet power of legend.