Introduction

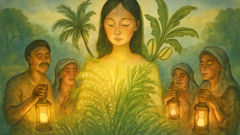

In Java, the morning begins with a shimmer. Dew pearls along the sawah, and a faint haze rises from the paddies as if the earth breathes gently before the day, as if it hums. Somewhere a rooster calls and the gamelan in a far-off pavilion wakes with a single, resonant note. This land has long believed that rice is not merely food; it is conversation with heaven, a green script written across hills and valley floors. Even now, elders tie small plaits of young rice to a carved figurine placed near the lumbung—a rice barn whose timbers know the weight of good seasons and the ache of lean ones. You see it in the offerings of yellowed palm, betel leaves, and the first grain of harvest: a quiet devotion to Dewi Sri, the Javanese goddess of rice and fertility. Her name softens mouths, her stories perfume the air, and her image—hair flowing like fields in wind—hangs above doorways to bless the house with enough. It’s said that long ago, before the people knew the comfort of steam rising from a pot of rice, the island trembled with hunger. Rivers hurried down volcanoes’ flanks, but the land had no memory of sowing, no ritual of first fruit, no green ladder of terraces climbing hills like steps to the gods. Then Dewi Sri arrived—born from longing and serpent-song, from the moral weave of the heavens and the sympathy of the underworld. She stepped into human time and changed it, and where she walked, the future laid itself like a mat woven of pandan leaves. This is her myth as it circles through the archipelago, turning with each retelling like a waterwheel, lifting shimmering buckets of wisdom from the river of what was and letting them fall onto the fields that keep us alive.

Child of Serpents and Soil

Before the first rice seed shivered in its husk, the heavens held court above Java’s sleeping mountains. Batara Guru, lord of the sky’s discipline, sat upon a throne supported by wind, cloud, and the whispered prayers of those not yet born. At the threshold of that palace coiled Antaboga, the ancient serpent whose body encircled the world’s still-forming edges. He was a guardian of patience, an old memory echoing through stone and root. Antaboga watched the empty places in the human future and felt a pang that resembled love. In that ache, in a wish shaped more by compassion than decree, Dewi Sri came into being—beautiful, luminous, and attentive, with eyes the color of rice grains just turning from green to ivory. Some say she rose from the serpent’s tear; others say she emerged from the seed-syllable of a forgotten mantra. Both could be true, for truth in myth is like water that accepts the cup that holds it.

She grew quickly around the palace, loved by the gentle and begrudged by certain gods who feared how much mortals might adore her. Antaboga taught her the secret silence of soil—the way it listens, the way it keeps memories of rain. The wind taught her to read the many guises of the sky. A visiting bird—so small its heart beat like ceremonial drumsticks—taught her to recognize hunger, not as a disaster, but as a message. Dewi Sri walked corridors pinstriped with light and shadow, and when she passed, ferns uncurled and small mosses glowed green as if their chlorophyll were prayer beads. Batara Guru saw this and wondered what use such tenderness had in a world that would soon harden with laws and bargains. She bowed to him, unafraid. “Father,” she said, using a name of respect, “I hear people in my dreams. Their bowls are empty, and their songs stop after one verse because there’s no breath for more.”

He turned from the balcony where the horizon shone like a blade. “There are fruits, tubers, fish,” he said. “There is enough. The world teaches itself endurance.”

“Endurance without hope,” she answered softly, “is a stone in the gut.” Her eyes lowered, as if she saw a harvest that did not yet exist—waves of green motes flickering across the land like murmuration. “I ask to go down and learn their names. I ask to hold their children. Let me help.”

Permission did not come like thunder. It came slowly, like a good rain. Batara Guru hesitated, fearing that if she descended she would never return to the cold exactness of the sky. Others murmured that mortals would confuse luck with worship, that order would unravel, that a single goddess smiling could tilt the scales of balance. Antaboga said nothing at first; his coils shivered faintly, like terraced hills about to be carved by brave hands. When he spoke, the court went quiet. “The earth without guidance is a drum without skin. It can be struck, but it produces no music. Dewi Sri was born from a wish with no owner but the world. If she longs to go, let longing be a guide. Longing built the riverbeds.”

And so the doors of the sky opened like two very large palms. Dewi Sri stepped through and felt the press of air change, smelled leaves roasting in hearth smoke, and heard the constant sound that is half water and half time. She landed at the edge of a clearing where women pounded tubers with patient rhythm. Villagers paused, not because a goddess blazed or thundered, but because a stranger had arrived with a gaze that knew them already. She dressed in simple cloth, the pattern dyed with a modest geometry that reminded the eye of irrigated steps on a mountainside. She learned their words and laughed with their children, who immediately hung on her every movement as if realizing their lullabies had just acquired a face.

Life then was stubborn. The forest was generous, yes, but hunger had a habit of slipping into evenings uninvited. People hunted with skill and fished with gratitude; still, there were months when the river ran sullen and the yam patches failed to swell. Dewi Sri sat with them around fires that bit the ankles with smoke and talked about water, about timing, about the memory that soil keeps if you take the trouble to listen. She scratched lines in the dirt, showing how to catch and guide streams, how to step the hillside so that rain would hesitate, pause its sprint, and bless longer. The first terraces were crude, then suddenly tidy, then remarkably beautiful, as if they had always waited under the slope’s skin for someone to free them. Families carried baskets, woven tight from rattan, and felt a new rhythm fill their bodies: plant, tend, hope, repeat.

In those days she wore no crown. A thin polished stick served as her tool. She walked barefoot and found that worms curled trustingly under her toes, that ants didn’t bite her, that the local monitor lizard nodded solemnly whenever she passed. When a child fell ill, she sat beside the mat wiping fevered skin with cooled water; when an elder died, she helped wash and shroud the body in quiet grief. Word of her spread as if carried by a hundred tiny kites. Strangers came—to barter, to ask for advice, to simply rest in the presence of a woman who radiated the sense that the world could, with care, feed itself.

Not everyone cheered. A god of tight ledgers and precise punishments visited in the shape of a noble with expensive rings. “Your work makes people forget the fear that built obedience,” he said, holding his hand so the rings clanged. “If their bowls are full, who will bow to laws?”

Dewi Sri looked past him to the paddies just beginning to reflect the sky. “People who are hungry will bow, yes. But hunger bows with its back and not its heart. Let their backs straighten. Then see what real respect is.” The noble bristled, but he was not a storm. He was only a passing cloud.

One night, as the moon scorched its path through a cloudless sky, Antaboga rose from the deep rock and water. Villagers felt a tremor and clutched their sleeping mats. Dewi Sri walked alone to the edge of the clearing. The serpent coiled near her, careful not to crush the young terraces. “Child,” he said. “The gods whisper of balance. They fear that your love will be like overwatering—a kindness that rots the root.”

She put a palm over his scaled snout. “I won’t drown them. I will teach them to plant hope in ground that holds it.”

“Then hear mine,” Antaboga murmured. “There is a kernel even my old tongue hesitates to describe. In it lies the pattern of a plant not yet born, one that will turn light and patience into food that sings. It is more than tuber, more than fruit. But it is impatient. It wants a body. It wants a vow.” He shifted and the soil trembled, releasing a fragrance like petrichor mixed with something sweet, unknown. “Be careful. The plant wants your life as its loom. If you accept, you won’t be able to return to the sky as you are.”

Dewi Sri listened, then laid her cheek against the ground. She couldn’t yet hear the plant’s voice, but she felt a pressure, an ache, like a seed swelling before its first hairline crack. She returned to the village and felt the gaze of people who had not slept well in weeks. The rains had paused. The yams sulked. Children drew slow circles in the dust with their toes. On the cooking stones, steam was a rare and precious sight. She reached into a basket and scattered small, pale shards—seeds she had been saving—from a plant no one had named. Birds watched without stealing. Dogs did not sniff. The seeds fell as if each had a voice and a destination, as if this were not a random scattering but a ceremony already promised in another world.

When morning came, villagers saw an unfamiliar green sheen over the paddies. The seedlings were thin, brave, and impossibly elegant. Dewi Sri waded into the flooded terrace, her sarong clinging to her thighs, and showed how to press each tender stalk carefully, spacing them like musical notes that would never crowd one another. The children laughed at how the seedlings seemed to vibrate when touched, like plucked strings. “They listen,” she said. “They understand rhythm.” The village exhaled; the mountain exhaled; even the river seemed to hum in a deeper register.

Meanwhile, up in the palace of regularities, Batara Guru frowned at the reports brought by birds and cautious spirits. A plant without precedent. A woman of compassion changing the cadence of a whole valley. He weighed the rumor like a coin. He imagined a future of festivals he didn’t regulate, of altars attended by gratitude rather than fear. Order, he decided, could not depend on everybody being hungry all the time. Yet a seed had been sown—on earth, yes, and in heaven. Seeds always lead to more than we bargain for.

The Sewing of Sacrifice

The new plant grew with a will. Its leaves cut the air in slender arcs. Its stalks were thin as wrists but held a promise that outweighed their fragility. Dewi Sri taught the people to care for it as if it could hear, because it could. She asked them to sing when they planted, to laugh when they weeded, to keep anger away from the terraces, for anger has a way of burning the unseen. Under her guidance, the village learned to move in a slow, deliberate ballet—the water bearers, the singers, the planters, and the watchers perched on scarecrow platforms, clapping to scare birds with more joy than menace. Children learned quickly; they walked the narrow bunds between fields with the balance of tightrope dancers. The river surrendered its old sulk. Rains remembered their cue.

With the plant came a new hunger in some. A minor deity of tempests, disguised as a headman from another valley, arrived, eyes shiny with covetous zeal. “You found a way to twist the sky into food,” he accused. “Who told you that you could take what belongs to gods?” Dewi Sri answered without raising her voice, “No one. I merely listened. The sky wanted to be eaten, and the earth wanted to be thanked.” He spat something that sizzled when it landed on a stone. That night, wind tripped on the eaves of houses and tugged at sleeping mats with rude hands. The young fields shivered. Dewi Sri rose and stood by the terraces, her hair drawn up like a hill itself, and faced the invisible tantrum. “If you have come to test strength, here is mine,” she said. “I will not fear a lesson.” The wind ran out of breath before dawn. The deity slunk away, embarrassed by his own noise.

But not all threats were storm and jealousy; some came in the shape of necessity. The plant’s promise sharpened and a rumor of famine reached them from upland communities. Runners with dust in their eyebrows delivered the news: the drought beyond the mountain had broken people’s calendars. Women chewed unripe fruit to keep hunger docile; men chewed patience. Dewi Sri weighed what they had. It wasn’t enough to share, not yet. She paced the bunds, ankle-deep in water, day after day, listening intently. At last she felt it—a summons rising from the mud like a thought that had waited politely for its turn to speak. She knelt and put both hands into the water. “I hear you,” she whispered to the plant that had no name because it was too new to need one. “I know what you ask. I won’t pretend I’m brave. But I can’t refuse.”

She gathered the village. Firelight spooled upward like gold silk. “There is a way to fill not just our bowls but the bowls of people we haven’t even met,” she said, her voice steady. “I was born from a wish. Now a wish speaks back to me and asks to be born from me.” A child asked, “Does it hurt?” She smiled at him as if she had been asked for a story before bed. “A little, then forever not at all.”

Don’t think of gods only as thunder. Don’t think of sacrifice only as knives. This is how it happened: Dewi Sri lay down on a mat woven with care and touched her brow to the earth. She asked the people to sing, not mourn. She asked them to hold one another’s hands so no one would fall into the ditch of grief. Antaboga rose at the edge of the gathering and circled, his coils a ring of protection. Batara Guru watched from a sky unstirred by wind, eyes unreadable as wet stone. Dewi Sri breathed slowly and closed her eyes, and as she did, a fragrance unfurled—a green sweetness with an under-memory of milk. Her body began to change, not with the brutality of injury but with the precision of ritual. Where her hair touched the mat, delicate grasses sprouted, the kind that later softened riverbanks. Her lips parted and from the damp of her breath came tiny white embryos, each like a pearl, each humming, each calling to the others the way siblings do when they have not yet learned words. Her eyes, those grains of light, warmed and multiplied. From her tears—tears of relief, not sorrow—sprang the first rice, thousands upon thousands of grains, orderly yet wild, each holding a little sun.

Her shoulders became the first coconut palms, tall and beneficent, their crowns murmuring with wind. Her arms dissolved into rows of bananas that curved like smiles in the shade. From the slope of her back came tubers fat with starch; from her chest the white, amply generous milk of a plant that would be boiled and drunk by young and old alike. Her fingers became chili plants to wake a meal into glory; her feet lengthened into sugarcane, to sweeten the bitter when needed. Around her hips a ring of pandan grew to flavor rice on festival days. Even her laughter found a plant-body, becoming lemongrass that people would bruise and breathe when colds came. It was a transformation not of punishment but of offering. Dewi Sri seemed to float, already a memory inside an enormous gratitude.

The people wept then—quietly, with hands over their mouths, because tears make poor salt in soup but potent water for faith. The elders collected the first rice grains that rolled like moonlets across the mat and placed them in a small basket lined with banana leaf. The basket was carried to the terraces with the reverence of a newborn, for it was exactly that: a birth, multiplied. Guided by Dewi Sri’s last gestures—half sign, half blessing—they broadcast the grains and then planted them in neat squares, singing the melody she had taught: a simple phrase about patience, water, light, repeated until the words lost their edge and became vibration.

Antaboga lowered his head, touching the edge of the transformed mat. “Child,” he said, neither sad nor glad, “you have woven the vow.” He lifted a single rice grain with the tip of his tongue and placed it on a flat stone that a woman had already set, as if she had expected the gesture. Batara Guru’s eyes softened like rain starting from mist. He understood then that order could be served by generosity as well as fear. He did not say it aloud. He simply exhaled, and the wind that returned to the valley was gentle, carrying the pollen of promise.

The days that followed were tender and exacting. Water levels had to be watched like a fussy child. New pests—emissaries of balance—appeared and were greeted not with war but with strategies. The villagers burned rice straw at the field’s edge to confuse insects, set up bamboo clappers to startle birds into seeking better conversation elsewhere, and laced their nights with stories so that fatigue did not gnaw at their tempers. The terraces themselves became amphitheaters for the opera of growth. Each leaf sharpened, each node thickened, and the heads of grain swelled, first demure, then assertive, then downright generous. Children learned to tell time by the changing posture of the plants: seedling bend, adolescent straightness, motherly bow.

Visitors came again, but different now. The upland runners returned with hollow cheeks but bright eyes. The village fed them not with charity but with kinship, for the grains that had swelled were many. A ceremony was invented—not from scratch but from memory that the world always had: women weaving a figurine from straw to honor Dewi Sri, men drumming softly as if coaxing the village’s shared heart to a steady beat, elders sprinkling water and murmuring words that sounded like rain taught to speak. They installed the figurine in the lumbung, decorating it with young coconut leaves and a garland of chilies and pandan. Children tucked flowers between its woven ribs as if the goddess might wake and ask for perfume.

One afternoon, when the rice was at what people later called the milk stage, Dewi Sri visited them in a dream so collective it felt like a warm wind that lifted everyone’s hair at once. “Treat me as you would your daughters,” she said. “Not as an idol who hoards respect, but as someone who brings you toward each other. Put aside rice for guests you have yet to meet. Thank the water that agreed to be measured. Thank the mud that agreed to hold you up.” When the people woke, their hands were already arranging leaves, parcels, and small offerings. They did not need instructions; the ritual had entered their muscles.

And what of the gods who had bristled? They watched the valley bristle instead—with life, with organization, with the kind of prosperity that grows slower than greed can imagine and lasts longer than greed can tolerate. The deity of tempests occasionally glowered from the mountain pass, raising a squall that knocked hats askew, but always someone would laugh and set the hat straight again. There was, now, a sturdiness in the village that storms could not scatter.

The Green Ocean and the Long Memory

Harvest came like a controlled joy. The heads of rice bowed low, heavy with the story they had absorbed. Dewi Sri’s teaching continued through the hands of the people—how to cut without waste, how to handle the sheaves as if they were breathing, how to listen for the small crunch that means the grain is ready to give itself. The first cut was made by the eldest woman, hands steady as plumb lines, and the first bundle was placed near the woven figurine with whispers that sounded suspiciously like gossip about happiness. Steam began to rise from kitchens not as a taunt to the hungry but as a public promise. When the pot lifted its lid, the aroma was the final truth: the sky had learned to feed the body.

News crossed ridges and ferried down rivers on bamboo rafts. Valleys far and near began to carve their own terraces. Methods varied with slope and soil, but everywhere the same principle held: water that lingers will multiply hope. Some carved steep ladders that matched the stern faces of their mountains; others coaxed shallow steps out of gentler hills that had long pretended to be indifferent. With each new set of terraces the island looked more and more like a great amphitheater built for an audience of clouds. Villages began to exchange songs. A boy from the coast taught inland children to whistle tunes borrowed from the sea. An upland grandmother taught fishing villages a square-shouldered dance that made everyone grin at their own awkwardness before learning the step.

In these gatherings, the myth of Dewi Sri ripened and reddened, took on local perfumes. The Sundanese told of her as Nyi Pohaci Sanghyang Asri, radiant and shy; in other valleys she wore different ornaments, different kin. The variations weren’t corrections; they were rivers that all understood they were part of the same sea. The core remained: a goddess who chose to be near, who let her body become the field where hunger is taught to be patient, then to vanish. Parents taught children to thank the rice before cooking, to pick up spilled grains as if they were precious jewels. When food got stuck to pots, nobody cursed, for it was simply more proof of life’s obstinate generosity.

When the Javanese shadow puppet stage—the wayang kulit—glowed with oil lamp light, dhalangs told Dewi Sri’s story between epics of princes and clowns and restless kings. Some nights, they gave her center stage. The leather silhouette of the goddess swayed with a dignity that felt like water wearing down stone. The audience leaned forward when the moment of transformation approached. Even though they knew what was coming, the hush fell as if for the first time. Children who couldn’t sit still for war stories sat cross-legged, rapt, when the puppeteer reached the part where a mat becomes a garden. Later, at home, those same children would tiptoe around the kitchen as if the mat there might suddenly sprout.

Rituals grew with the fields. At wiwitan—the first-fruits ceremony—the community made offerings at the lumbung, tying up a young rice sheaf like a bride’s hair, teasing it with flowers and laughing so she wouldn’t be shy. Sedekah bumi gatherings honored the soil as a generous elder: people laid out plates of rice tinted yellow with turmeric, greens slick with coconut milk, fish salted and grilled until their skins shone like night. They thanked Dewi Sri and the ancestors for partnership, because one without the other is a drumbeat missing its echo. Nyadran, the pilgrimage to graves, threaded the myth into memory. Families swept tombs clean, offered rice and flowers, and spoke to those who had become the invisible furniture of their lives, asking that their unseen hands continue guiding the young away from trouble and toward honest work.

As the years braided themselves like ropes, other trials came. Insect plagues that learned to recognize the smell of a good banquet. Merchants who tried to turn rice into a mirror for greed. A governor who wanted to tax the harvest until gratitude soured into resentment. The people had been taught not just how to plant, but how to remember. They remembered that abundance is not a private trophy. They left small packets of rice at river bends for travelers in too much hurry to roast their own fish. They kept a spare mat handy for the stranger who arrived after the evening drum had called the hour of rest. And when the governor’s men came with paper like knives, grandmothers taught the young how to sit in front of the lumbung and sing until morning, not moving, not threatening, simply occupying the space where rice met air. The governor learned that you can’t tax a song that refuses to end. He took less, and the people sang him on his way, not in mockery but in relief.

Time painted its layers. A boy who had once balanced on a narrow levee became the father who waited for rain like a letter. A girl who had cried at the wayang’s moment of transformation became the woman whose hands knew exactly how to lift hot rice with no waste, no fuss, moving grains from pot to bannered plate with an expertise that made her daughters watch and memorize. Artisans carved Dewi Sri’s image with new motifs—sometimes as a regal goddess crowned with rice fronds, sometimes as a young wife with a basket on her hip, sometimes a serpent coiling at her feet as if the earth itself were a pet that needed stroking.

Centuries later—if centuries can be shucked like husks—cameras arrived. Tourists, well-meaning, pointed lenses at terraces that remembered feet more than eyes. The people smiled and taught the visitors to step on the levees without crumbling the edges, to fold their hands in the evenings when the mountain’s shadow entered the valley like a guest. They told the story of Dewi Sri in Bahasa Indonesia, in Javanese, in body language robust enough to cross any grammar. They taught them a word—cukup: enough. It is a word like a fence low enough to step over when your neighbor has less, high enough to keep out those who have nothing to offer but hunger with teeth.

Even in contemporary kitchens ruled by flicked switches and precise timers, rice still insists on being washed with thoughtful turns of the wrist, the way elders do. The first steam is still a blessing that fogs the face. When the lid lifts, small faces still rise on tiptoe, and the old myth unfurls like a banner you didn’t realize you’d hung at the back of your heart. Dewi Sri’s straw figurines remain in some homes, replaced each harvest with the same shy smile, the same careful tilt of the head, as if listening for the small talk of grain. Others honor her with modern shrines—photographs, green ribbons, a carved spoon that has stirred decades of dinners. The language changes, the devotion does not.

What remains the most surprising is that her myth doesn’t ask to be believed so much as practiced. Plant something. Share the first of it. Bring a bowl when you visit. Remember that the floor of a kitchen is not a battlefield, and if a few grains fall, pick them up and kiss them back into the pot. When disaster comes—and it will—the myth provides choreography. People line up: those with firewood, those with water, those with hands that know how to make toddlers giggle even when their stomachs protest. The terraces, from above, still look like a green ocean pausing mid-tide, obedient to the moon of patience. At night, when the lamps are low, it’s easy to imagine that the goddess passes each window, checking if there is enough, leaving behind the scent of pandan and something wiser than sweetness.

Now and then, a child asks where Dewi Sri went after her body became the fields. The simplest answer is the truest: she went everywhere the rice went. She is in the lumbung where grain rustles like tiny laughter. She is in the wet footprints in a kitchen as someone drains a pot. She is in the cards of advice delivered by elders who pretend to be stern and fail with a smile. Ask where she is and it’s the same as asking where gratitude is resting today. Find gratitude and you find her, often near a stove, sometimes on a levee, sometimes reflected in a kettle lid just before it fogs.

Conclusion

If you listen closely in the early hours on Java, you’ll hear the myth doing its daily work. A wooden ladle taps a pot. A door opens to the fields; someone steps out to examine the water shining in the terraces like liquid mirrors. The world adjusts its shawl of mist, and the rice whispers the one thing it’s always said since Dewi Sri made her vow: patience. This is not patience that grinds; it’s the sort that makes room for everything to arrive on time. The myth of Dewi Sri is a calendar, an ethics lesson, and a love story hidden in plain view. It teaches that food is an agreement between the sky and the ground, that sacrifice can be a transformation rather than a wound, and that community isn’t a slogan but the practice of sharing warmth and work. From ancient ritual to modern kitchens, from wayang stages to harvest fields, her presence widens the horizon. To tell her story is to accept an invitation: be tender with the earth, be exact with gratitude, make enough and share it. In every bowl of rice, a landscape gathers—terraces, rain, hands—and in every spoonful, the goddess keeps her promise, grain by grain.